I’ve been teaching for a rather long time. Most of my professional career, in fact. Which is odd, since I had decided at age 13 that I wanted to make buildings.

Well… Actually, at age 13, I wanted to “get paid to color all day.” And at that time, I figured that meant making buildings. After all, every architect I knew at that time (there were a lot, btw) were doing just that—getting paid to color all day. So clearly, that was the job for me!

So I went to architecture school. And I colored for a number of years. But about 8 years into it, I realized I wasn’t coloring as much as I thought I should be. Instead, I was organizing information, talking to contractors, drawing lines, and trying to develop documents designed to help people make buildings. Which is not nearly as fun as I thought it would be.

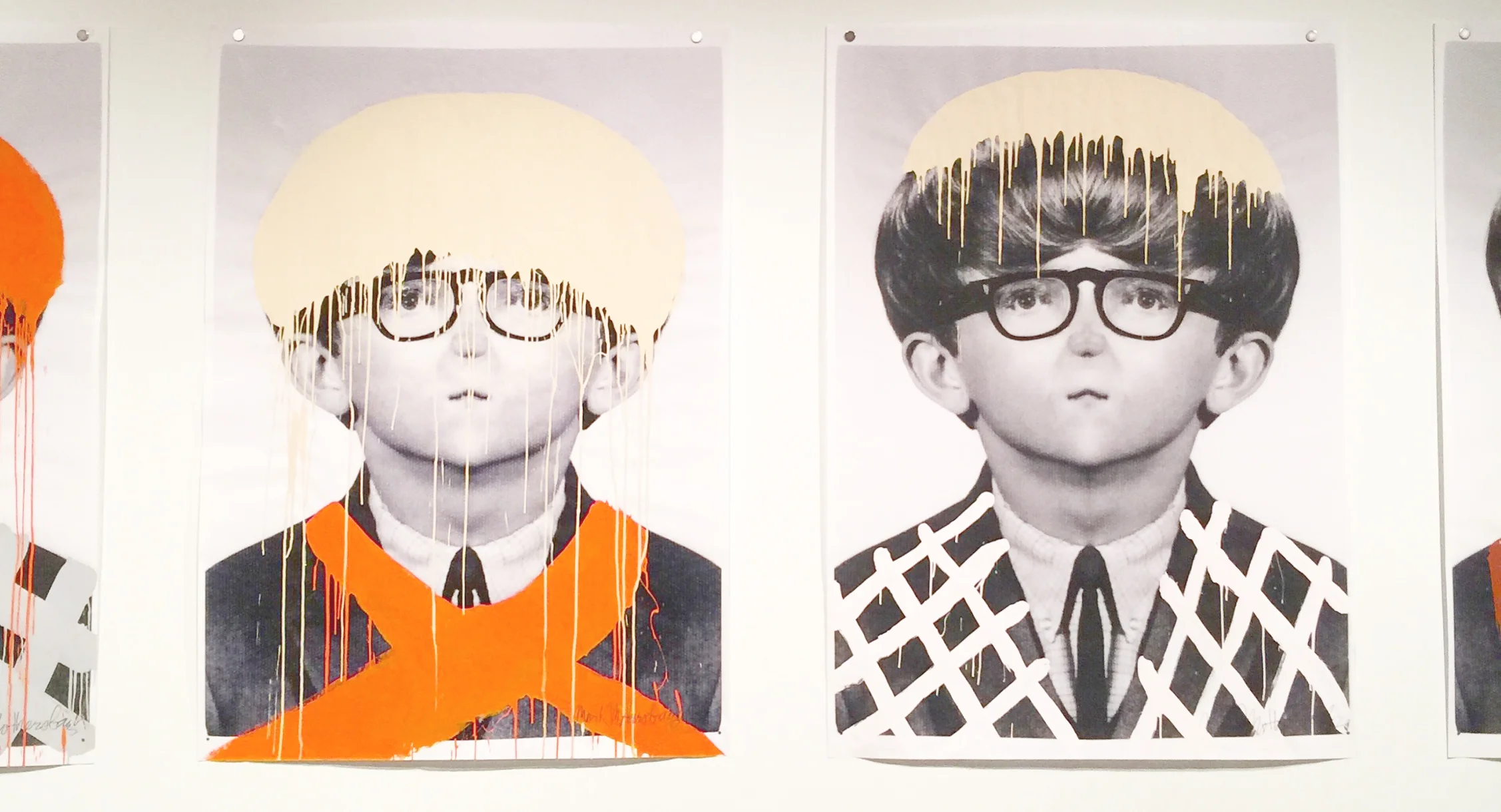

But I still got paid to color every once in awhile, when I was asked to put together client presentations. This was a coveted task in the office, since it meant we got paid to… color. Usually, this job fell to me, primarily because I apparently had a good sense of architectural color (black, white, gray, orange, and blue—any of these were sure to please!), and I really liked Futura (look! Letters made from circles and lines!!!). So I spent some (but not nearly enough) of my time as an architect putting together presentations and…coloring.

Then the economy turned, as it is wont to do. And suddenly, I found myself in need of a new career. Architecture suffers more than most careers when economies turn, since people who might hire architects tend to decide it’s cheaper to paint and re-carpet their existing buildings than it is to pay someone to design something entirely different.

In the course of 6 months, we went from hiring hoards of people to laying off nearly all of them. It was brutal. And it meant there was a glut of architects out there, all looking for work. Best to jump ship and find something closer to my dream “coloring” job.

At this point, I moved—rather arrogantly—into graphic design. After all, I’d been trained to design as an architect, which meant I knew how to use grids and organize information on a page. “Surely this is all graphic designers do,” I thought, as I designed my first logo (brand mark!!!), developed my first web page (in Macromedia Flash 3!), and announced to the world that I had opened for business.

Luckily, I had the foresight to limit my audience. I specialized in designing websites and print collateral for architecture firms and architecture schools, since I’d found success catering to this audience in the office environment. The leap made sense. And for awhile, it worked well. I had a lot of clients, and everyone seemed very pleased with what I was producing. Things were good.

But, as with all things grown ups must face, I found myself needing more income. Clients were established, but the big-paying “let me design your site from scratch” projects dried up rather quickly. So, I started asking around for side gigs. And a local graphic designer (who I’d established a strong email mentor-based relationship with) forwarded me to a friend of theirs at the local community college.

My first class was teaching color studies. It was a Photoshop skills class, with a concentration in color relationships and theory. So I was supposed to show students how to color in Photoshop. No. Really. It sounded too good to be true!

Finally, after nearly a decade in the professional world, I was literally being paid to color with no external expectations (like making buildings, or making slideshows for clients). And as terrified as I was at the prospect of standing in front of a room full of (potentially judgmental) eager youths, I was more excited at the prospect of having found my place in the market. Was this the new career path I was looking for? (Please please please please.)

Yes.… And no. Or at least, not yet.

I taught at this community college, and at the local state university (in the architecture department, teaching first-years how to draw) for about 18 months. And then opportunities dried up for my husband. Strange how that happens—just as one of us finds footing, the other one loses theirs. But it happened. So we moved.

In our new city, I went to work as a wayfinding designer, which meant I was paid to make signs that told people where to go. It was an interesting mixture of graphic design and architecture with a hint of human behavior (why do they keep turning left when we’ve clearly told them to go straight ahead?!?), and I actually loved doing it. But I missed teaching more. So, once we knew my husband’s career was more secure, I left this world of arrows and architecture and went back into teaching.

This time, I threw myself head first into the task, eliminating all external distractions. In other words, I made it my full-time focus.

Well… Sort of. I also enrolled in a remote MFA program, which I used as a resource of information which I could apply to my own teaching. I’m not saying I copied assignments or lectures or anything like that! But I certainly did use the resources my education provided to craft my own teaching voice.

Great system, this “teaching while learning” model, if you can pull it off! Exhausting. But your students totally get that you understand what they’re going through, since they see you going through it too. I actually think being a student while teaching full time gave me more cred in the classroom. It was an unusual bond I’ve not found again since I graduated.

But, I digress. Totally digress. Because this was supposed to be about my teaching philosophy, which I developed while experiencing this student-teacher dual personality. And what it's evolved into as I now teach in the online classroom.

Anyway. The philosophy. Apparently, every teacher needs a philosophy. It isn’t enough to go into a classroom each day, stand in front of the students, and just tell them what you know. Anyone can do that. Just watch any YouTube tutorial, and you’ll realize it’s possible.

No. Instead, you need to have a philosophy, or running internal dialog that helps you make decisions about what you’ll present, how you’ll present it, and what you hope the students come away from it with. It’s sort of like branding—what impression do you want your audience to have of you? What is your core message? What are the strategies and tactics you use to get that message across?

So… what's the philosophy, then?!?

My philosophy (aka "brand") embraces the idea that design is, and should always be, first and foremost fun. I mean, hey. We’re going to be doing this stuff for at least 45 years, yes? Maybe even longer, depending on the type of life we live? We should probably try to enjoy it, right? If we take it, and ourselves, too seriously, we lose touch with what brought us to design in the first place. I wanted to color—that, inherently, is fun. If I try to fuss about, nudging images and text over by half pixels (which is, literally, impossible), I’m not having fun.

Same goes in the classroom. I can teach rules. Or I can teach ideas. Ideas are fun. Rules are not.

So, in the classroom, my philosophy begs me to teach ideas—to excite the students, calling them to an action of “fun.” I invite them to run towards that cliff’s edge, just to see how far down the drop might be.

That said, I do have a few tenants I follow, to keep them—and me—from crashing on rocks down below…

First. Do no harm. Remember that anything you tell a student will be taken as the word of “god.” Make sure you know what you’re talking about. If you don’t, be honest and tell them you don’t know. Then, work with them to find out. Honesty earns cred every time, and rarely, if ever, undermines it.

Second. Look to the past to find the strengths. Each designer (and future designer) is a product of their past. They come to you (the teacher) with certain strengths in hand, even if they don’t know this. Talk to them about their experiences to find those strengths. Then, help that student build upon those strengths in ways that open their imaginations.

Second, restated. Really, look to the past. Design doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It came from somewhere. Even modernism, which came from a desire to turn away from the past, has the past behind it to push it forward. Embrace that. Own that. Help your students get that, too.

Third-ish. Work the process. All designers have a process. Teach one that works, and help the students understand why it works. But avoid a linear process. The best designs come from a messy, but exciting, back and forth between different voices and ideas. If you teach that design is messy and (potentially) illogical, you can help students learn to think more critically, which helps them solve all sorts of problems down the road.

… Ugh, (1, 2, 2.5, 3….) Learn from your peers, and let them learn from you. Set up a community of sharing and learning, where all people have an equal voice. As the teacher, you have to be the moderator. But don’t shut down the conversation just because it’s not going in your pre-described direction. Let the students learn from each other, while you learn from them as well.

Another one. Explore, experiment, play, and fail. Hard. Always. Enough said.

Last one. For now. Know when your work (aka “the student” or “the student’s work”) is strong enough to stand on its own. We finesse everything we do to the nth degree to a fault. Sometimes, we have to recognize that letting it go is the best way for it to grow.

Now, I should state that these don’t always work. They certainly are not a checklist. Every class in every environment is different, and things need to stay flexible enough to adjust as needed. But they’re a good starting point. And they’ve worked well for me.