The next few posts will cover lessons learned while watching students of Miami University explore various Italian cities during our Knowhere study abroad program. All content is my (and the students’) intellectual property.

“Wayfinding is a dynamic affair.”—Romedi Passini, Wayfinding in Architecture

Breadcrumbs. Well, visual breadcrumbs to be more specific. Many people consider wayfinding elements—signage, directory maps, arrows and other navigational symbols—to be a series of visual breadcrumbs that help people figure out where they are and where they need to go. Much like the story of Hansel and Gretel, where two small children toss breadcrumbs while being lead along a wandering path, wayfinding elements lead people from place to place, point to point, crumb to crumb, until they safely find their desired destination. It’s there to help. It’s there to lead. It’s there to keep people from feeling lost.

Down and dirty, we hold an understanding of how the space around us is arranged. Typically, this system is organized hierarchically—local, regional, national, universal—in relation to our location and things around us. I am here. That path is over there. It leads me to the main intersection that takes me to the grocery store and many other destinations that wind in and out of the landscape. That mountain in the distance is much further away than the stream I can see snaking around its base and through the valley below me. I can get to that stream by following a number of different paths, some of which I can see, others I can’t. For most, we locate things in our world based on our understanding of ourselves within this grand scheme.

Regional understanding of Rome by Knowhere student

But sometimes people understand the world as a more linear progression, where one thing leads to another, much like the breadcrumbs idea. We remember that to get to the store, a specific series of instructions must be followed. Drive to the end of the street. Turn left at the stop sign. Turn right at the main road. The store is just past the school. We understand that paths work with each other to develop a network, but we may not fully understand how that network organizes on a larger scale, and exactly where our familiar landmarks fall within this system.

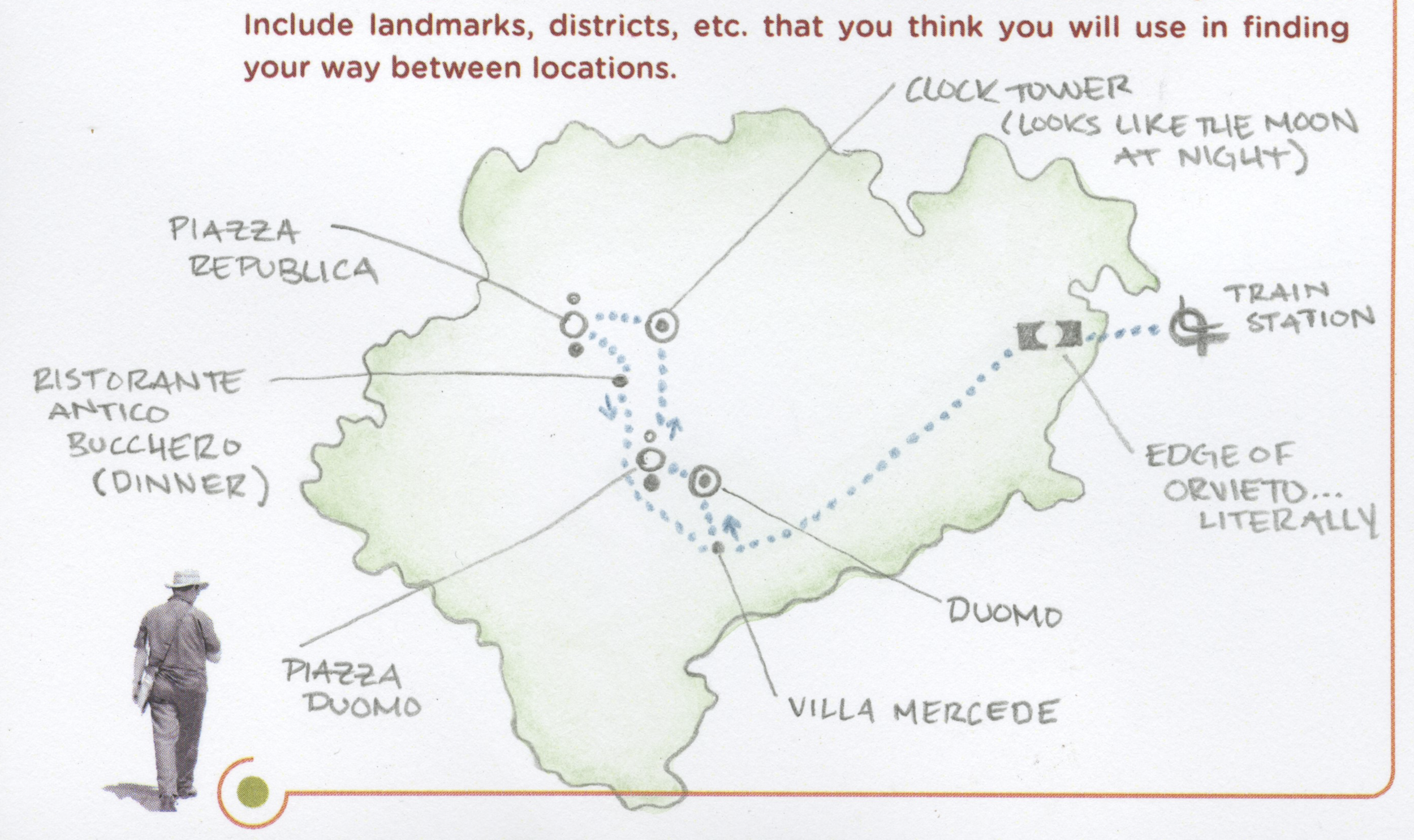

Linear progression of Knowhere students through Orvieto, Italy

Wayfinding designers, people who develop systems to help others navigate through complex spaces, realize that these two types of spatial understanding exist. And they try to work within both understandings when designing these systems. Wayfinding designers develop elements that orient and lead, such as signage, maps and other environmental clues. Orientation is the main intention of wayfinding, and leading is its primary tool.

But how does wayfinding actually work?

Wayfinding literally means finding one’s way. In the realm of graphic design, it is further defined as a subset of environmental graphic design concerned with the development of graphics elements that help people navigate an area or building. Based primarily around patterns of urban organization, wayfinding designers have found that people will rely on three basic layers when navigating or trying to recall a location. These are:

color

text/numbers

image (pictograms, arrows, etc.)

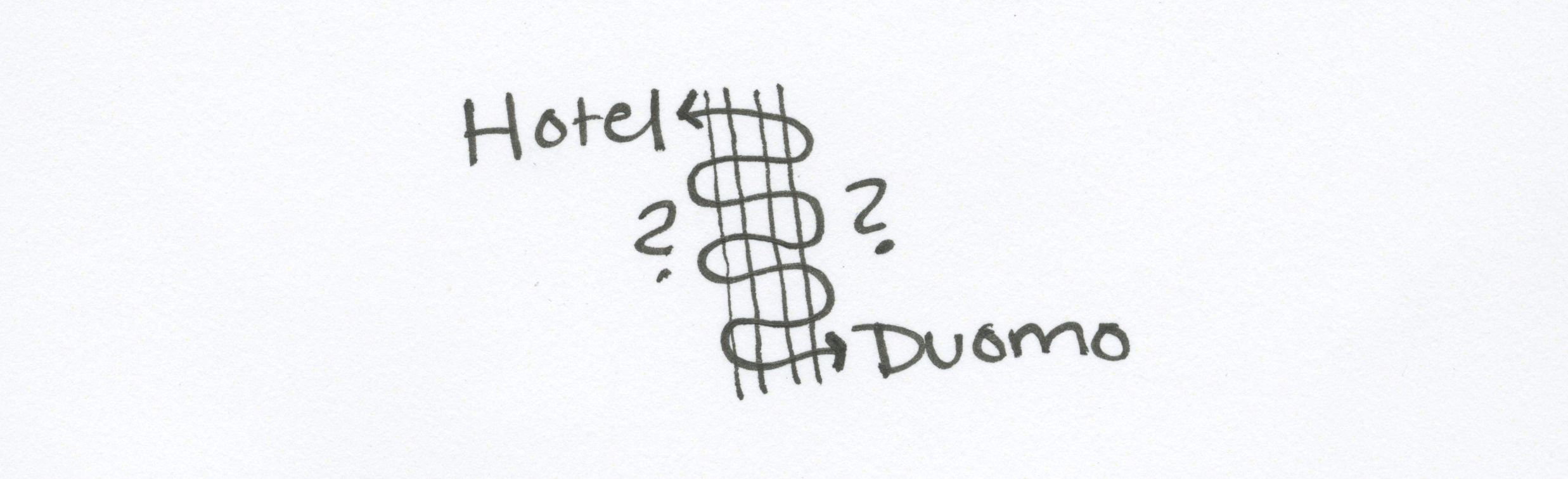

Knowhere student interpretation of travel to Duomo di Milano from the hotel

Though this might be an oversimplified way of looking at it. Perhaps we should consider the following definition as well:

“Wayfinding” was the term introduced to describe the process of reaching a destination, whether in a familiar or unfamiliar environment. Wayfinding is best defined as spatial problem solving. Within this framework, wayfinding comprises three specific but interrelated processes:

Decision making and the development or a plan of action

Decision execution, which transforms the plan into appropriate behavior at the right place in space

Information processing understood in its generic sense as comprising environmental perception and cognition, which, in turn, are responsible for the information basis of the two decision-related processes

—Arthur and Passini, Wayfinding: People, Signs, and Architecture

So why do we need it in the first place? Over the next few posts, we’ll be looking into how this might be answered.

“To become completely lost is perhaps a rather rare experience for most people in the modern city.”—Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City